Stratigraphic Guide

Home | Preface | Intro | Principles | Definitions | Stratotypes | Litho | Unconformity | Bio | Magneto | Chrono | RelationshipsChapter 9. Chronostratigraphic Units

A. Nature of Chronostratigraphic Units

Chronostratigraphic units are bodies of rocks, layered or unlayered, that are defined between specified stratigraphic horizons which represent specified intervals of geologic time.

The units of geologic time during which chronostratigraphic units were formed are called geochronologic units.

The relation of chronostratigraphic units to other kinds of stratigraphic units is discussed in Chapter 10.

B. Definitions

1. Chronostratigraphy

The element of stratigraphy that deals with the relation beteween rock bodies and the relative measurement of geological time.

2. Chronostratigraphic classification

The organization of rocks into units as a representation of geological time.

The purpose of chronostratigraphic classification is to organize systematically the rocks forming the Earth’s crust into named units (chronostratigraphic units) that represent intervals of geologic time (geochronologic units) to serve as references in narratives about Earth history including the evolution of life.

3. Chronostratigraphic unit

A body of rocks that includes all rocks representative of a specific interval of geologic time, and only this time span. Chronostratigraphic units are bounded by isochronous horizons which mark specific moments of geological time.

The rank and relative magnitude of the units in the chronostratigraphic hierarchy are a function of the durations they represent.

4. Chronostratigraphic horizon (Chronohorizon)

A stratigraphic surface or interface that is isochronous, representing everywhere the same moment in time (i.e., they are of the same age).

C. Kinds of Chronostratigraphic Units

1. Hierarchy of formal chronostratigraphic and geochronologic unit terms

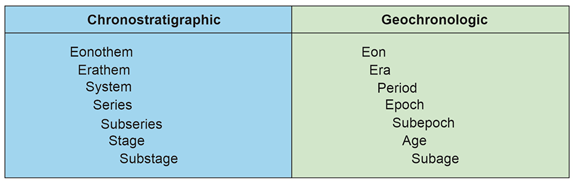

The Guide recommends the following formal chronostratigraphic terms and geochronologic equivalents to express units of different rank or time scope (Table 3).

Table 3: Hierarchy of Formal Chronostratigraphic and Geochronolgic Units

2. Stage (and Age)

The lower and upper boundary stratotypes of a stage represent specific moments in geologic time, and the time interval between them is the duration of the stage (i.e, named age).

a. Definition

The stage includes all rocks deposited between two chronostratigraphic horizons defined by GSSPs. A stage is the lowest ranking unit in the chronostratigraphic hierarchy that can be recognized on a global scale.

b. Boundaries and stratotypes

A stage is defined by its boundary stratotypes. These are sections that contain a designated point in a stratigraphic sequence of essentially continuous deposition, preferably marine, chosen for its correlation potential.

The selection of the GSSPs of the stages of the Standard Global Chronostratigraphic Scale deserves particular emphasis because they serve to define not only the stage boundaries but also chronostratigraphic units of higher ranks which are subseries, series, systems and erathems.

c. Time span

The lower and upper boundary stratotypes of a stage represent specific moments in geologic time, and the time interval between them is the duration of the stage. Currently formally defined stages vary widely in duration. The thickness of the strata in a stage and its duration are independent variables of widely varying magnitudes.

d. Name

The name of a stage should be derived from a geographic feature in the vicinity of its stratotype or type area.

In English, the adjectival form of the geographic term is used with an ending in “ian” or “an”. The age takes the same name as the corresponding stage.

3. Substage (and Subage)

A substage is a subdivision of a stage whose equivalent geochronologic term is subage.

Since a substage is a subdivision of a stage it will be restricted primarily to a regional scale.

A more detailed definition will be provided after a discussion in the ISSC.

4. Subseries (and Subepoch)

a. Definition

A subseries is a chronostratigraphic unit ranking immediately above stages and below a series. It consists of one or several consecutive stages.

The geochronologic equivalent of a subseries is a subepoch.

b. Boundaries and boundary-stratotypes

Subseries are defined by the boundary stratotypes of the bounding stage(s) (see Section 9.H).

c. Time span

See Section 9.D.

d. Name The names of currently recognized subseries are derived from their position within a series: Lower, Middle, Upper. A new subseries name should be derived from a geographic feature in the vicinity of its stratotype or type area.

Names of geographic origin should preferably be given the ending “ian” or “an”.

The subepoch corresponding to a subseries takes the same name as the subseries except that the terms “Lower” and “Upper” applied to a subseries are changed to “Early” and “Late”.

5. Series (and Epoch)

a. Definition The series is a chronostratigraphic unit ranking above subseries or stages and below a system. A series consists of several consecutive subseries, or (when subseries are not used) of several consecutive stages.

The geochronologic equivalent of a series is an epoch.

b. Boundaries and boundary-stratotypes Series are defined by the boundary stratotypes of the bounding subseries and stages (see section 9.H).

c. Time span See section 9.D.

d. Name

A new series name should be derived from a geographic feature in the vicinity of its stratotype or type area. The names of most currently recognized series, however, are derived from their position within a system: Lower, Middle, Upper.

Names of geographic origin should preferably be given the ending “ian” or “an”.

The epoch corresponding to a series takes the same name as the series except that the terms “Lower” and “Upper” applied to a series are changed to “Early” and “Late”.

e. Misuse of “series” The use of the term “series” for a lithostratigraphic unit more or less equivalent to a group should be discontinued.

6. System (and Period)

a. Definition

A system is a unit of major rank in the conventional chronostratigraphic hierarchy, above a series and below an erathem. A system is composed of several consecutive series.

The geochronologic equivalent of a system is a period. As an exception, the rank of subsystem (Mississippian, Pennsylvanian) is used for the Carboniferous System.

b. Boundaries and boundary-stratotypes

The boundaries of a system are defined by boundary-stratotypes (see Section 9.H).

c. Time span

The time span of the currently accepted Phanerozoic systems varies broadly.

d. Name

The names of currently recognized systems are of diverse origin inherited from early classifications: some indicate chronologic position (Paleogene, Neogene, Quaternary), others have lithologic connotation (Carboniferous, Cretaceous), others are tribal (Ordovician, Silurian), and still others are geographic (Devonian, Permian).

Likewise, they bear a variety of endings such as “an”, “ic”, and “ous”. There is no need to standardize the derivation or orthography of the well-established system names. The period takes the same name as the system to which it corresponds.

7. Erathem (and Era)

An erathem is a chronostratigraphic unit greater than a system consisting of several systems.

The geochronologic equivalent of an erathem is an era.

The names of erathems in the Phanerozoic were chosen to reflect major changes of the history of life on Earth: Paleozoic (old life), Mesozoic (intermediate life), and Cenozoic (recent life). Eras carry the same name as their corresponding erathems.

8. Eonothem (and Eon)

An eonothem is a chronostratigraphic unit greater than an erathem. The geochronologic equivalent is an eon. Three eonothems are generally recognized, from older to younger, the Archean, Proterozoic and Phanerozoic eonothems. The combined first two are usually referred to as the Precambrian.

The eons take the same name as their corresponding eonothems.

9. Nonhierarchical formal chronostratigraphic units - the Chronozone

a. Definition

A chronozone is a formal chronostratigraphic unit of unspecified rank, not part of the hierarchy of formal chronostratigraphic units. It is the body of rocks formed anywhere during the time span of some designated stratigraphic unit or geologic feature. The corresponding geochronologic unit is the chron.

b. Time span

The time span of a chronozone is the time span of a previously designated stratigraphic unit or interval, such as a lithostratigraphic, biostratigraphic, or magnetostratigraphic polarity unit.It should be recognized, however, that while the stratigraphic unit on which the chronozone is based extends geographically only as far as its diagnostic properties can be recognized, the corresponding chronozone includes all rocks formed everywhere during the time span represented by the designated unit. For instance, a formal chronozone based on the time span of a biozone includes all strata equivalent in age to the total maximum time span of that biozone regardless of the presence or absence of fossils diagnostic of the biozone.

c. Geographic extent

The geographic extent of a chronozone is, in theory, worldwide, but its applicability is limited to the area over which its time span can be identified, which is usually lesser.

d. Name

A chronozone takes its name from the stratigraphic unit on which it is based, e.g., Exus albus Chronozone, based on the Exus albus Range Zone.

D. The Standard Global Chronostratigraphic (Geochronologic) Scale

1. Concept

A major goal of chronostratigraphic classification is the establishment of a hierarchy of chronostratigraphic units of worldwide scope, which will serve as a standard scale of reference for the dating of all rocks everywhere and for relating all rocks everywhere to world geologic history (See Section 9.B.2). All units of the standard chronostratigraphic hierarchy are theoretically worldwide in extent, as are their corresponding time spans.

2. Present status

The Standard Global Chronostratigraphic (Geochronologic) Scale can be found in the International Chronostratigraphic Chart.

E. Regional Chronostratigraphic Scales

The units of the Standard Global Chronostratigraphic (Geochronologic) Scale are valid only as they are based on sound, detailed local and regional stratigraphy.Accordingly, the route toward recognition of uniform global units is by means of local or regional stratigraphic scales. Moreover, regional units will probably always be needed whether or not they can be correlated with the standard global units.It is better to refer strata to local or regional units with accuracy and precision rather than to strain beyond the current limits of time correlation in assigning these strata to units of a global scale. Local or regional chronostratigraphic units are governed by the same rules as are established for the units of the Standard Global Chronostratigraphic Scale.

F. Subdivision of the Precambrian

The Precambrian has been subdivided into arbitrary geochronometric units called Global Standard Stratigraphic Ages (GSSA) but it has not been subdivided into chronostratigraphic units recognizable on a global scale with the exception of the Ediacaran system/period.

There are prospects that chronostratigraphic subdivision of much of the Precambrian may eventually be attained through isotopic dating and through other means of time correlation. However, the basic principles to be used in subdividing the Precambrian into major chronostratigraphic units should be the same as for Phanerozoic rocks, even though different emphasis may be placed on various means of time correlation, predominantly isotopic dating.

G. Quaternary Chronostratigraphic Units

The basic principles used in subdividing the Quaternary into chronostratigraphic units are the same as for other Phanerozoic chronostratigraphic units, although the methods of time correlation may have a different emphasis.

H. Procedures for Establishing Chronostratigraphic Units

See also Section 3.B.

1. Boundary stratotypes as standards

The objective of defining chronostratigraphic units is to specify time spans for the description of Earth history. This is achieved by defining specific horizons as representatives of designated instants of geologic time.

The boundaries of a chronostratigraphic unit of any rank are defined by two designated reference points in the rock sequence, the lower and upper boundary-stratotypes of the unit. The two points are located in the boundary-stratotypes of the chronostratigraphic unit which need not be part of a single section. Both, however, should be chosen in sequences of essentially continuous deposition since the reference points for the boundaries should represent points in time as specific as possible (see Section 9.H.3).

2. Advantage of defining chronostratigraphic units by their lower boundary stratotypes

The definition of a chronostratigraphic unit places emphasis in the selection of the boundary-stratotype of its lower boundary; its upper boundary is defined as the lower boundary of the succeeding unit. This procedure avoids gaps and overlaps in the Standard Global Chronostratigraphic Scale.

For example, should it subsequently be shown that the selected horizon is at the level of an undetected break in the sequence, then the unrepresented span of geologic history would belong to the lower unit by definition and ambiguity is avoided.

3. Requirements for the selection of boundary stratotypes of chronostratigraphic units

Chronostratigraphic units offer the best promise of being identified, accepted, and used globally and of being, therefore, the basis for international communication and understanding because they are defined on the basis of stratigraphic horizons that are globally correlatable. Particularly important in this respect are the units of the Standard Global Chronostratigraphic (Geochronologic) Scale. The term “Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point” (GSSP) has been proposed for the standard boundary-stratotypes of the units of this scale.

In addition to the general requirements for the selection and description of stratotypes (section 4.C, boundary-stratotypes of chronostratigraphic units should fulfill the following requirements:

- The boundary-stratotypes must be selected in sections representing essentially continuous deposition.The worst possible choice for a boundary-stratotype of a chronostratigraphic unit is at an unconformity.

- The boundary-stratotypes of Standard Global Chronostratigraphic Units should be in marine, fossiliferous sections without major vertical lithofacies or biofacies changes.Boundary stratotypes of chronostratigraphic units of local application may need to be in a nonmarine section.

- The fossil content should be abundant, distinctive, well preserved, and represent a fauna and/or flora as cosmopolitan and as diverse as possible.

- The section should be well exposed and in an area of minimal structural deformation or surficial disturbance, metamorphism and diagenetic alteration, and with ample thickness of strata below, above and laterally from the selected boundary-stratotype.

- Boundary stratotypes of the units of the Standard Global Chronostratigraphic Scale should be selected in easily accessible sections that offer reasonable assurance of free study, collection, and long-range preservation. Permanent field markers are desirable.

- The selected section should be well studied and collected and the results of the investigations published, and the fossils collected from the section securely stored and easily accessible for study in a permanent facility.

- The selection of the boundary stratotype, where possible, should take account of historical priority and usage and should approximate traditional boundaries.

- To insure its acceptance and use in the Earth sciences, a boundary stratotype should be selected to contain as many specific marker horizons or other attributes favorable for long-distance time correlation as possible.

The IUGS International Commission on Stratigraphy is the body responsible for coordinating the selection and approval of GSSPs of the units of the International Standard Global Chronostratigraphic (Geochronologic) Scale represented in the International Chronostratigraphic Chart (ICC).

I. Procedures for Extending Chronostratigraphic Units-Chronocorrelation (Time Correlation)

Only after the limits of a chronostratigraphic unit have been established at the boundary-stratotypes can the unit be extended geographically beyond the type section. The boundaries of chronostratigraphic units are synchronous horizons by definition. In practice, the boundaries are synchronous only so far as the resolving power of existing methods of time correlation can prove them to be so.

All possible lines of evidence should be utilized to laterally extend chronostratigraphic units. Some of the most commonly used are:

1. Physical Interrelations of strata

The Law of Superposition states that in an undisturbed sequence of sedimentary strata the uppermost strata are younger than those on which they rest.

The determination of the order of superposition provides unequivocal evidence for relative age relations.

All other methods of relative age determination are dependent on the observed physical sequence of strata as a check on their validity. For a sufficiently limited distance, the trace of a bedding plane is the best indicator of synchroneity.

2. Lithology

Lithologic properties are commonly influenced more strongly by local environment than by age. The boundaries of lithostratigraphic units eventually cut across synchronous surfaces, and similar lithologic features occur repeatedly in the stratigraphic sequence. Even so, a lithostratigraphic unit always has some chronostratigraphic connotation and is useful as an approximate guide to chronostratigraphic position, at least locally.

Distinctive and widespread lithologic units also may be diagnostic of general chronostratigraphic position.

3. Paleontology

The orderly and progressive course of organic evolution is irreversible with respect to geologic time and the remains of life are widespread and distinctive.

For these reasons, fossil taxa, and particularly their evolutionary sequences, constitute one of the best and most widely used means of tracing and correlating beds and determining their relative age. However, biostratigraphic correlation is not necessarily time correlation.

4. Isotopic age determinations

Isotopic dating methods (U-Pb, Rb-Sr, K-Ar, Ar-Ar) based on the radioactive decay of certain parent nuclides at a rate that is constant and suitable for measuring geologic time provide an additional key to chronostratigraphy. However, not all rock types and minerals are amenable to isotopic age determination.

Isotopic dating contributes age values expressed in years and has furnished quantitative evidence of the length of geologic time.

In some circumstances, isotopic age determinations of volcanic and other igneous rocks provide the most accurate or even the only basis for age determination and chronostratigraphic classification of sedimentary rocks.

Discrepancies in age determinations may arise from the use of different decay constants. It is, therefore, important that uniform sets of decay constants recommended by the IUGS Subcommission on Geochronology be used.

5. Geomagnetic polarity reversals

Periodic reversals of the polarity of the Earth’s magnetic field are utilized in chronostratigraphy, particularly in Mesozoic and Cenozoic rocks where a magnetic time scale has been developed. Polarity reversals are, however, iterative and cannot be identified without the assistance from some other method of dating such as biostratigraphy or isotopic dating.

6. Paleoclimatic change

Climatic changes leave imprints on the geological record in the form of glacial deposits, evaporites, red beds, coal deposits, faunal changes, etc.

Their effects on the rocks may be local or widespread and provide valuable information for chronocorrelation, but they must be used in combination with other specific methods.

7. Paleogeography and eustatic changes in sea level

As a result of either epeirogenic movements of land masses or eustatic rises and lowerings of sea level, certain periods of Earth history are characterized worldwide by a general high or low stand of the continents with respect to sea level. The evidence in the rocks of the resulting transgressions, regressions, and unconformities can furnish an excellent basis for establishing a worldwide chronostratigraphic framework. The identification of a particular event, however, is complicated by local vertical movements and so the method requires auxiliary help in order to identify the events correctly.

8. Unconformities

Even though a surface of unconformity varies in age and time-value from place to place and is never universal in extent, certain unconformities may serve as useful guides to the approximate placement of chronostratigraphic boundaries.

Unconformities, however, cannot fulfill the requirements for the selection of such boundaries (see Section 9.H.3).

9. Orogenies

Crustal disturbances have a recognizable effect on the stratigraphic record. However, the considerable duration of many orogenies, their local rather than worldwide nature, and the difficulty of precise identification make them unsatisfactory indicators of worldwide chronostratigraphic correlation.

10. Other indicators

Many other lines of evidence may in some circumstances be helpful as guides to time-correlation and as indicators of chronostratigraphic position.

Some are more used than others, but none should be rejected.

J. Naming of Chronostratigraphic Units

A formal chronostratigraphic unit is given a binomial designation - a proper name plus a term-word - and the initial letters of both are capitalized.Its geochronologic equivalent uses the same proper name combined with the equivalent geochronologic term, e.g., Cretaceous System - Cretaceous Period.

The proper name of a chronostratigraphic or geochronologic unit may be used alone where there is no danger of confusion, e.g. “the Aquitanian” in place of “the Aquitanian Stage”. See sections 3.B.3 and 3.B.4.